Edward William Lane was a pioneering British lexicographer, ethnographer, and Egyptologist in the 19th century. Over the course of his time in Egypt, Lane would produce a series of important ethnographic, anthropological, and linguistic texts. Although his first attempt at documenting his travels—a set of objective observations and notes called Description of Egypt—was unsuccessful, Lane’s subsequent work did prove to be more popular. His ethnographic study An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, his translation of Thousand and One Nights, and, perhaps most importantly, his unfinished Arabic-English Lexicon were all celebrated at the time for their depth and verisimilitude. To cite Geoffery Roper: “[o]ne of Lane’s predominant characteristics throughout his life was a meticulous, even obsessive, thoroughness in everything he undertook.”[1] Documenting his travels in Egypt—from the people he met and the places he visited to the language he spoke—became his greatest undertaking and obsession.

Lane was born in the English town of Hereford in 1801. First home schooled by his mother, and then sent to a Grammar School in the town of Bath, Lane showed a talent for mathematics early in his academic career. Following a “traumatic” experience visiting his brother at Cambridge, Lane became disillusioned with the college lifestyle. In part because of his brother’s alcoholism, and in part because of his own reserved personality, Lane would never set foot on a university campus as a student again.[2] Having exhausted what he thought were all of his “academic” options, Lane began to explore a career in skilled labor as an apprentice engraver. Here, Lane was first exposed to the rediscovered Egyptian world.

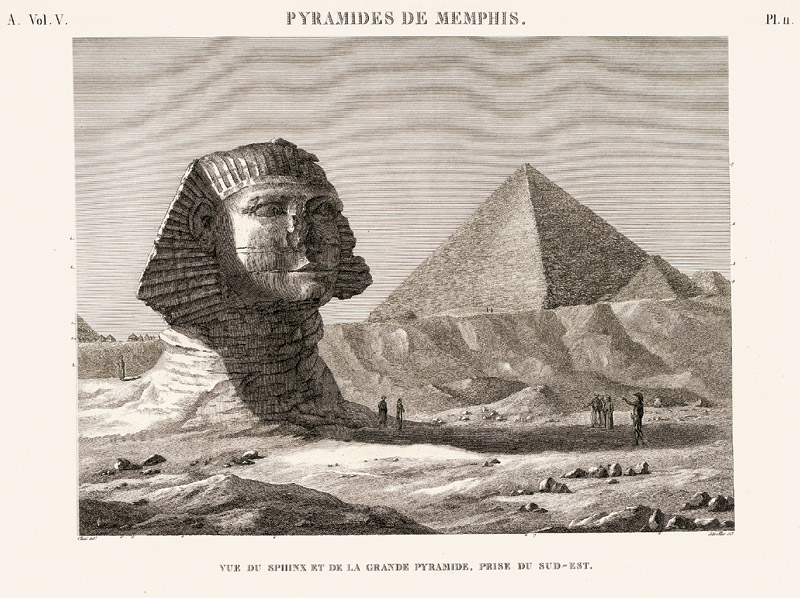

By the early 19th century, Britain was being flooded by hundreds of folios containing illustrations of Egyptian archaeological and historic sites. Description de l’Egypte–Napoleon Bonaparte’s comprehensive description of his Egyptian conquest in 1799–contained more than 3,000 engravings. The more widely available travel account Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypte by Denon also contained hundreds of well known and distributed illustrations.[3] Given the popularity of these works, it would be very likely that Lane was exposed to both. As an engraver, Lane would have been tasked with arduously replicating these images onto metal plates so they could be printed and sold.

Illustrations aside, Lane attended one of Belzoni’s magnificent exhibitions in London during the summer of 1821. Giovanni Baptista Belzoni was famous–or rather infamous–for discovering and exporting artifacts from ancient Egyptian tombs. Seeing the history and majesty of Egypt first hand further inspired Lane to pursue Egyptology as a field of academic study.

What originated as a passion for ancient Egypt soon began to broaden into an interest in contemporary Egyptian people and society.[4] To those ends, Lane began an intense study of Arabic, intending to reach some level of competency in the language before he departed. This proved to be a monumental task. With little outside help, Lane managed to learn the bare minimum to communicate with the Egyptians he first encountered. He did this without any tutoring and with limited access to translated texts. It was around this time–when Lane was about 24 years old–that an unfortunate bout of illness ground his education to a halt, and, wanting to seek warmer climates before he was further incapacitated, Lane set sail across the Mediterranean. That year–1825–marked the beginning of the journey that would consume the rest of Lane’s academic life.

In some of the notes for the manuscript of Lane’s unpublished book Description of Egypt, he included a passage in which he shared some of what he felt as he first saw Alexandria—the Mediterranean port city where he would first set foot in Egypt—from his ship.

As I approached the shore, I felt like an Eastern bridegroom, about to lift up the veil of his bride, and to see, for the first time, the features which were to charm, or disappoint, or disgust him. I was not visiting Egypt merely as a traveler, to examine its pyramids and temples and grottoes, and after satisfying my curiosity, to quit it for other scenes and other pleasures: but I was about to throw myself entirely among strangers; to adopt their language, their customs and their dress; and, in associating almost exclusively with the natives, to prosecute the study of their literature. My feelings therefore, on that occasion, partook too much of anxiety to be very pleasing.

E.W. Lane and Jason Thompson, Description of Egypt: Notes and Views in Egypt and Nubia, Made During the Years 1825, -26, -27, -28 (Cairo: Oxford University Press, 2000), x.

Lane’s objective in Egypt was to observe and analyze the architecture and ruins of the ancient Egyptian civilization, but also to analyze and document the lives of his still living Egyptian peers. Egypt’s contact with the West was rapidly changing both its political and economic structure. Muhammad Ali’s reign from 1805-1848 forever changed Egyptian society. His campaign for Westernization–now called defense developmentalism–forced Egyptians to rapidly adapt to a new way of life. Lane and others saw the social and societal changes forced by Muhammad Ali and his team of reformers and wanted to preserve what they could of the ‘old’ Egyptian culture.

Unfortunately, Lane’s attempt to lift the “veil” of Egypt has since been problematized by modern scholars like Edward Said. Lane’s contribution to discourse on the Egyptian ‘other’—especially in Manners and Customs—was informed by a strict adherence to the protocol of the “rational observer.” His sterile, direct prose gave his readers the impression of objectivity, even though his perspective was skewed by the implicit position of power he held: the power of the observer, the power to diagnose the Egyptian people and their society—even subconsciously, and the power to omit or include what he saw or heard. Lane’s interpretation of the events he experienced was altered by his frame of reference, and his blend of narrative and ‘fact,’ combined with an overwhelming attention to detail, gave his work a sense of truthfulness it otherwise might not have had. Edward Said first discovered the connection between Lane’s scholarship and implicit power in his groundbreaking work Orientalism. Although Said was correct in identifying the system that provided Lane with the power to comment on the Egyptian ‘condition,’ he also unnecessarily attacked Lane’s style, character, and methodology.

Said claims that Lane acted in secret and invaded Egyptian spaces. Lane would cloak himself in the disguise of colloquial Arabic, wear Egyptian dress, and be observant of Egyptian customs so that he could “prosecute the study of their literature.” He would live—as Said says—two lives: “the Oriental one for engaging companionship (or so it seems) and the Western one for authoritative, useful knowledge.” Lane “ironically enter[ed] the Muslim pattern only far enough to be able to describe it in a sedate English prose”—which provided him with a level of authority and legitimacy that he otherwise would not have.[5] Said’s criticism of Lane has since been the subject of a long and protracted scholarly debate. Proponents of Lane’s work have worked hard to defend his documentation of Egyptian culture.

Upon arrival in Cairo, Lane immediately began looking for a place to stay in a wealthy Egyptian neighborhood. In Manners and Customs, he tells stories about being rejected from an apartment because he did not meet one important criteria: he was still single. Lane claims: “[t]o abstain from marrying when a man has attained a sufficient age, and when there is no just impediment, is esteemed, by the Egyptians, improper, and even disreputable.” After getting kicked out of a house for being a bachelor, Lane found himself a suitable apartment to conduct his work. Even in his new home, Lane was constantly harassed by a neighboring sheikh for the same reasons. Lane recounts how the Sheikh would say: “’You tell me,’… ‘that in a year or two you mean to leave this country: now, there is a young widow, who, I am told, is handsome, living within a few doors of you, who will be glad to become your wife, even with the express understanding that you shall divorce her when you quit this place; though, of course, you may do so before, if she should not please you.’”[6] To resist the sheikh, Lane made an excuse. Because he had already seen that the woman in question had a remarkably beautiful face, and because his stay in Egypt was temporary, Lane told the sheikh he was worried that he would be unable to divorce his new bride once he left. The sheikh was not satisfied, but Lane ended the story there. Lane did in the end achieve some domestic bliss; he possessed and then later married a slave girl named Nafeeseh.

Lane litters these little glimpses into his personal life throughout his work–although he never loses sight of the big picture. This anecdote can be found in a chapter of Manners and Customs called “Domestic Space–Continued” where Lane explores the Muslim institution of marriage and the home. During the years Lane was writing about Egypt–the first segment from 1825 to 1828, and the second from 1833 to 1835–he spent most of his time recording his experiences and existing in Muslim spaces. Part of the novelty of Lane’s ethnographic work is the way Lane can be both very specific and very general at the same time. Lane blends his omniscient narration with real first person narrative. This juxtaposition of style gives Lane a real level of authority he otherwise might not have.

For example, we can examine a few passages from a chapter of Manners and Customs called “Superstitions.” Lane opens this chapter by examining the Jinn. In Islam, Jinn are a kind of low level angel that can interact with the human world and possess people. Lane begins this section by making one of his not-so-subtle generalizations:

“THE Arabs are a very superstitious people; and none of them are more so than those of Egypt. Many of their superstitions form a part of their religion; being sanctioned by the Ckoor-a’n; and the most prominent of these is the belief in Ginn, or Genii—in the singular, Gin’nee.”[7]

Not one page further, Lane jumps into an anecdote about the time he went to see some pranksters pretending to be Jinn by throwing bricks at pedestrians from the tops of buildings. In the following passage, Lane is referring to one of his Egyptian friends that has heard about English theater and makes a comparison between these pranksters and English “comedy.”

“One of my friends observed to me, on this occasion, that he had met with some Englishmen who disbelieved in the existence of genii; but he concluded that they had never witnessed a public performance, though common in their country, of which he had since heard, called koomedlyeh (or comedy); by which term he meant to include all theatrical performances. Addressing one of his countrymen, and appealing to me for the confirmation of his words…”[8]

The Egyptian friend continues by describing the theater in London where the “koomedlyeh” takes place. He goes in depth about the lights and majesty of the show, and notes that English theater must in part have been an act of the Jinn. Lane finishes by saying that none of his explanations for the magic of British theater convinced the Egyptian man of the reality. As if the statement “the Arabs are a very superstitious people” is justified by this story, Lane quickly moves on. Lane consistently interlaces the first person with his otherwise dry narrative. His experiences prove his generalizations and vice versa.

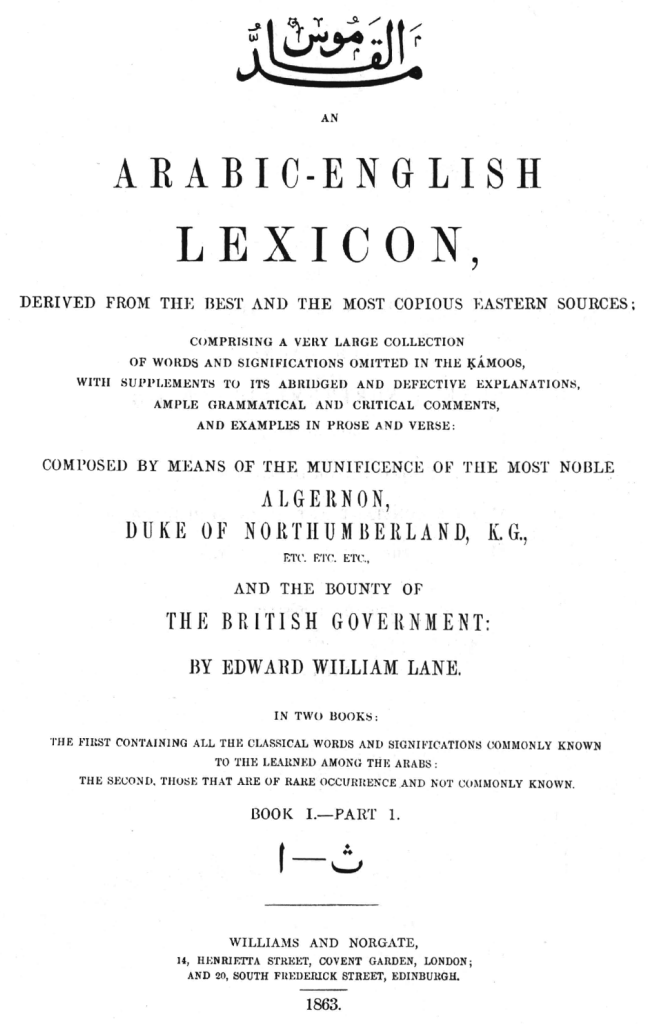

Lane’s final and most important project was his Arabic-English Lexicon. Although it was never fully completed, the Lexicon is Lane’s most ambitious and most impressive project. By working with his friend Ibrahim al-Disuqi, Lane was able to compile a dictionary of Arabic terms translated into English. It was rare at the time for Arab and Western scholars to work as amicably as Lane and Disuqi did. In his notes, Disuqi included this on Lane–calling him by his nickname Mansur Effendi:

Amongst those who came to us during the fifties, arriving from distant lands that have extensive knowledge, skillful workmanship, and excellent masterpieces, to receive some language books and to translate them into English, is proficient Mansur Effendi, who has skillful intelligence. He is a man of refined manners joined with the jewels of virtue, distinguished from his own people by his brilliant acumen, and amicable manners. [9]

The above passage was cited as (Mubarak, A/-__ XI: 10) and can be found in: Suha Kudseih, “Beyond Colonial Binaries: Amicable Ties among Egyptian and European Scholars, 1820-1850,” Journal of Comparative Poetics 36 (2016): 59.

The Arabic-English Lexicon consumed the rest of Lane’s life. Unfortunately, before the work was finished, Lane and al-Disuqi had a falling out over. Apparently, although “al-Dasuqi had known all along that Lane was not Muslim,” Lane’s “affect to believe in things such as jinn, the blessings of holy men, and magic” was so convincing “that he thought they had a shared cosmology.” It was “humiliating” for al-Disuqi “to learn that Lane had been detached all along, using him, patronizing him, perhaps even mocking him, just to make him more forthcoming with information.”[10] This anecdote also in confirms Edward Said’s thesis that Lane entered Muslim spaces only so far as he needed to learn from the Egyptian people.

In the end, Lane’s Arabic-English Lexicon is perhaps the most uncontested and important–at least in the contemporary sense–work that Lane produced. It has since been used as a reference in other later Arabic-English translations. It was the first and most ambitious project of its time.

Although Edward William Lane’s life and legacy have been contested in the 20th century, the body of his work provided European scholars with a glimpse into the lives of modern Egyptians. By studying their habits, superstitions, language and lives, Lane textualized a people and established a mode for their further study. What I find most impressive about Lane and is work is his unending and undying passion for honest scholarship. His legacy aside, what Lane truly represented the beginning of the Orientalist era in the scholarship of the middle east.

[1] Geoffrey Roper, “Texts from Nineteenth-Century Egypt: The Role of E.W. Lane,” in Paul and Janet Starkey, Travelers in Egypt (New York: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 1998), 244.

[2] Jason Thompson, Edward William Lane: The Life of Pioneering Egyptologist and Orientalist (Cairo: American university in Cairo Press, 2000), 14.

[3] Ibid., 17.

[4] E.W. Lane and Jason Thompson, Description of Egypt: Notes and Views in Egypt and Nubia, Made During the Years 1825, -26, -27, -28 (Cairo: Oxford University Press, 2000), x.

[5] Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Random House, Inc., 1978), 160-161.

[6] E.W. Lane, An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians: Written in Egypt during the Years 1833, -34, and -35, Partly from Notes Made during a Former Visit to that Country in the years 1825, -26, -27, and -28, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 193.

[7] E.W. Lane, An Account of …, 283.

[8] E.W. Lane, An Account of…, 287-288.

[9] The above passage was cited as (Mubarak, A/-__ XI: 10) and can be found in: Suha Kudseih, “Beyond Colonial Binaries: Amicable Ties among Egyptian and European Scholars, 1820-1850,” Journal of Comparative Poetics 36 (2016): 59.

[10] Thomson, 635.