Egyptian mummies have been a point of fascination and creative inspiration for authors and poets alike since their first uncovering by Western Europeans around the turn of the 19th century. This common fascination comes in part due to the mysterious and unnatural appearances of the embalmed bodies. Their shrunken frames and petrified features are hardly a comforting sight. Despite their harrowing appearances Mummies were not always the monsters that we think of them today. Long before their first movie appearance as the now renown locked arm, bandage wrapped monsters, mummies played a wide range of roles. They were used for public entertainment, satirical poetry and social commentary. In fact, it wasn’t until the mid 1900’s that mummies were first used as a “monster.” The transformation of mummies from spectacle to villain is one that can be tracked through the public’s fascination with the fictional, mystical powers and history of ancient Egypt. This transformation can be drawn back several centuries and is directly corelated to western popular culture’s long-standing, unfounded, fascination in Ancient Egyptian mysticism and the supernatural.1 John Ray. The Rosetta Stone and the Rebirth of Ancient Egypt. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007. 4.

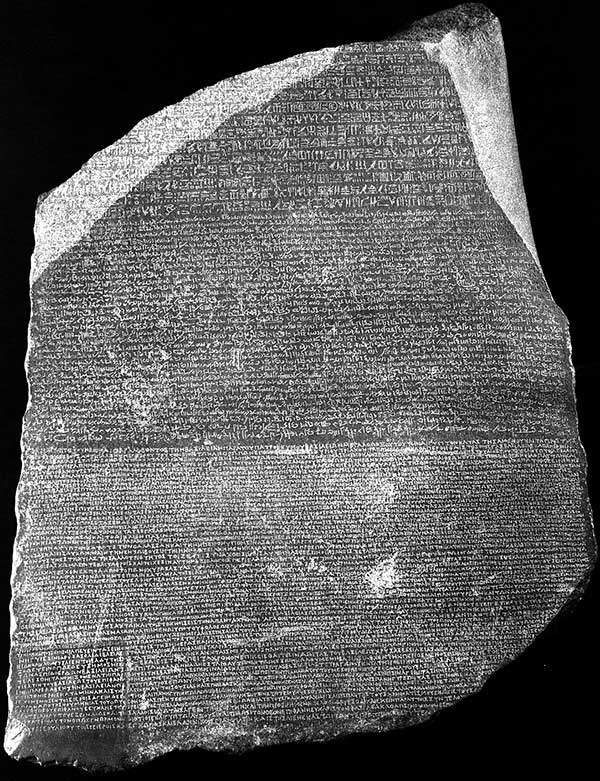

The capture of the Rosetta Stone and other archeological discoveries peaked English curiosity in the unknown and mysterious world of what would come to be known as Ancient Egypt. Expositions, such as Giovanni Battista Belzoni’s recreation of Pharaoh Seti I’s tomb in 1821 in London and Bristol, only aided in English curiosity into the seemingly long-lost world of Ancient Egypt. The exhibitions and recovered archeological finds were quite popular with Victorian elites, and became prized possessions for museums and wealthy nobles alike. Mummies also became figures of public spectacle in the mid 19th century with creation of mummy unwrapping exhibitions. The popularity of the unwrappings created meteoric rise in the acquisition of mummies in the 1820’s by Europeans as they were now highly desirable artifacts for collection and display. 2 Beverley Rogers. “Unwrapping the Past Egyptian Mummies on Show.” In Popular Exhibitions, Science and Showmanship, 1840-1910. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016. 199. Mummies also became feature points at Victorian parties, where they would be unwrapped and publicly displayed for all partygoers to see. 3 Natasha, Wynarczyk. “Uncovering the Dead at a Victorian Mummy Unwrapping Party.” Vice News, 2016. While the theatrical nature of the unwrappings seems brutish to the modern eye, they were quite on-par with other scientific experiments and discoveries of the time.

In the 19th century it was not uncommon that scientists and inventors would turn their discoveries into public displays and exhibitions. Electricity is a good example of a discovery that quickly left the lab for the stage, and it is a discovery that will play a critical role in the history of the mummy in western popular culture. Scientist Lugi Galvani discovered that when an electrical current passed through an animal it caused it to move and shake. This discovery inspired other scientists to try similar experiments on living and dead animals. Galvani’s nephew, Giovanni Aldini, ended up popularizing the experiments by creating public exhibitions where he ran electrical currents through dead animals and made them seemingly move about as if they were alive.4 Kirsty Chilton. “Dr. Thomas Joseph Pettigrew, a.k.a. “Mummy Pettigrew”: A Short Biography.” The Old Operating Theatre & Herb Garret. October, 2016.

The experiments were eventually performed on human corpses, with Aldini performing perhaps his most famous experiment on the body of executed murder, George Foster in 1803 at Newgate Prison. Aldini place rods in and around Foster’s corpse, and when charged they pulsed through Foster’s body, making his jaw clench, hands tighten into fists and his legs shake. 5André Parent. “Giovanni Aldini: From Animal Electricity to Human Brain Stimulation.” Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences, Vol. 31, Issue 4. 2004. 576. Many of the onlookers, “thought that the wretched man was on the eve of being restored to life.” 6 George Theodore Wilkinson. The Newgate Calendar c.1820. ‘The Making of Modern Law: Trials, 1600-1926. London: Woodworth Editions, 1997. 64. In fact one of the surgeons present at the experiment died soon after his return home of freight.7 George Theodore Wilkinson. The Newgate Calendar c.1820. ‘The Making of Modern Law: Trials, 1600-1926. London: Woodworth Editions, 1997. 64. The story of Foster’s “reanimation” became popular amongst the British masses and it inspired many creative minds to toy with the idea of electrically charged human revival. One inspired author was Mary Shelly, who used the idea electric reanimation to create one of her novel’s main characters, Frankenstein’s Monster.

Frankenstein was released in 1818, the book’s popularity, along with growing popular belief in electronic reanimation soon mixed with mid 19th century England’s fascination with mummies to create a new genre of literature, the Mummy genre. Mummies in this genre weren’t monsters, but were instead a far more versatile character, especially when compared to their 21st century counterparts. Mummies were used to provide social commentaries, or for satirical pieces poking fun at popular beliefs. They almost always were brought back to life using some kind of electricity, and they often possessed some kind of super natural or inhuman qualities.

The first book to include a reanimated Egyptian mummy was written in 1827 by Jane Webb, titled, The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century. The mummy in this story is reanimated through electricity, and proves to be quite friendly, offering political and societal advice. 8 Jane Webb. The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century. London. 1827 Webb was believed to be inspirited to write the book due to the rise in popularity of Ancient Egypt and the science fiction genre during the mid 19th century. It is even speculated that she may have attended a mummy unwrapping some years before writing the novel. In 1845 Edgar Allen Poe released his first story to include a mummy, Some Words With a Mummy. Poe’s story follows a man who is invited to watch the unwrapping of a mummy at a doctor’s house. Once unwrapped the mummy proves to be in good condition and the men decide to try and reanimate it, instead of dissect it, as one usually would. They use electricity to awaken the mummy, Allamistakeo, 9 The name itself is meant to be a humorous one, sounding like a failed magical spell more than an actual Egyptian name. who, once awoken, condemns the men for their barbaric treatment of his body. They apologize and all present company, mummy included, sit down for wine and cigars. It is during their chat over wine that Allamistakeo informs the men that ancient Egyptians lived for 800 years, and that their embalmment was meant to be more of hibernation than a death. He continues to tell many other stories that mythologize ancient Egyptians.10Poe, Edgar Allen. Some Words With a Mummy. American Review: A Whig Journal, 1845. Poe’s story built on the growing popular belief in a mystical Ancient Egypt, a belief that would continue to grow and expand as the century went on.11 Freeman, Richard. “The Mummy in Context.” European Journal of American Studies. Vol 4.1. (2009). 1

The mystical powers of Ancient Egypt grew in popularity as the 19th century enter its latter half, due in large part to the literary fiction about it. Authors began playing with the idea of curses, and the supernatural, giving mummies powers more liken to gods than mortal men.12 http://Books and Films such as The Mummy’s Foot, 1840, and Smith and the Pharaohs, 1912, used the idea of mummies having super natural powers, but they did not yet make mummies into monsters or vengeful beings. Instead they were merely adding to the growing mythology around a mystical Ancient Egypt. The first novel to use the theme of a vengeful mummy was, The Beetle, by Richard Marsh in 1897. In Marsh’s book the vengeful mummy was, “born of neither God nor man.”13 Richard Marsh. The Beetle. New York & London: Putnam’s Sons The Knickerbocker Press, 1897. It is a hypnotic, shapeshifter, that follows the British politician who opened his tomb, bringing about misfortune and curses upon the defiler. The book was quite popular and even beat out its supernatural literary counterpart, Dracula, which was released in the same year. The popularity of The Beetle pushed mummies into the horror and thriller field of creative writing.

The newfound role of mummies as vengeful, supernatural beings was solidified in 1923 when fiction met reality after the untimely death of Lord Carnarvon. The Lord was the primary funder of the excavation and exhumation of Pharaoh Tutankhamen tomb and mummy, a story that I will explain later. He died April 5, 1923, experiencing “a high fever, severe pain, pneumonia in both lungs, and eventually heart and respiratory failure.”14“Lord Carnarvon’s death.” Times. April 6, 1923. Carnarvon was the only member of the team who entered the tomb to pass away and mysterious circumstances and timing of his death led many to speculate he was cursed by the vengeful spirit of Pharaoh Tutankhamen. 15 Cox, Ann M. “The Death of Lord Carnarvon.” The Lancet. Vol 361, Issue 9373. 2003. The Lord’s death caught the attention of the papers and the public’s imagination alike, which had been running wild since the tomb’s discovery a year earlier.

The discovery of “King Tut’s”16 King Tut was the abbreviated, westernized nickname given to Tutankhamen by the English and American public. I will be using his full name and abbreviated one interchangeably. tomb in 1922 was an international sensation, but archeologists wanted to keep the press away from the site so speculations and rumors about the tomb we common. One rumor in particular was popular amongst western readers, and that was that the translated words above the entrance to King Tutankhamen tomb said, “Death comes on wings to he who enters the tomb of a Pharaoh.”17 Cox, Ann M. “The Death of Lord Carnarvon.” The Lancet. Vol 361, Issue 9373. 2003. The claim would have likely come and gone like other rumors had Lord Carnarvon not died soon after entering the allegedly cursed tomb a year later. The discovery of “King Tut” followed by the Carnarvon’s mysterious death brought Ancient Egypt back into the forefront of popular culture’s imagination, nearly one hundred years after its original apex in popularity. People held King Tut parties, and novels and movies all rushed to capture the public’s new fascination with Egyptian mysticism and the Pharaoh’s curse. Ancient Egypt was so popular in the 1920’s that fashion designers even started basing dresses around the patterns and jewelry found in King Tut’s tomb.18 Sean Munger. “When Egypt was cool: The “Tutmania” craze of the 1920’s.” March, 2014.

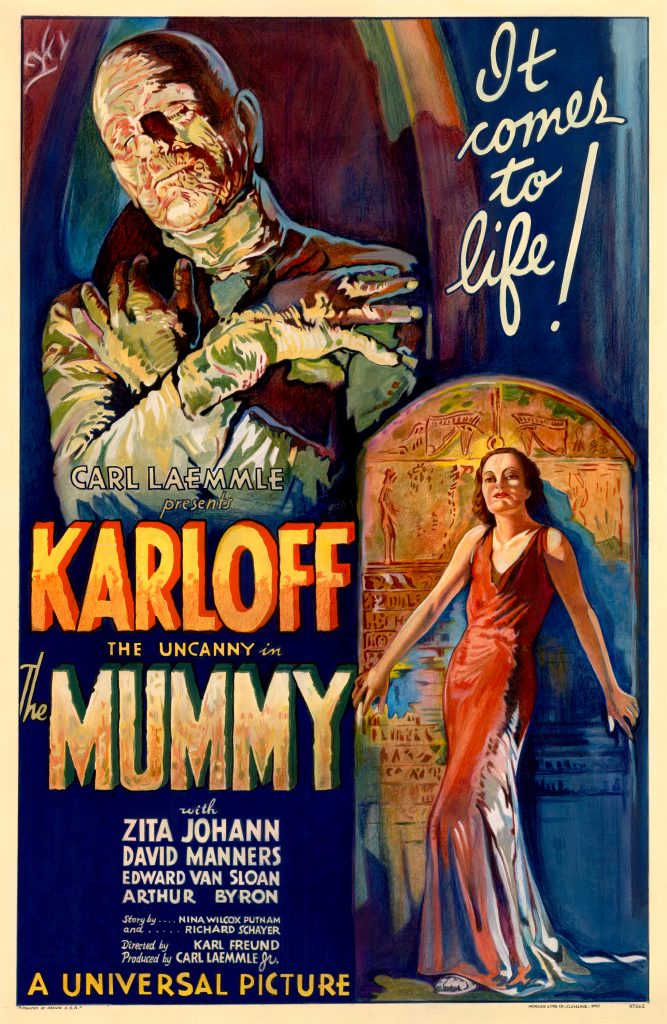

By the end of the decade Ancient Egypt was still a popular theme for creatives, but the Great Depression that started in 1929 made the creation of literary works expensive. Movies on the other hand, while not unaffected, still proved to be quite popular during the depression. Their low admission costs, and brief reprieve from the difficulties of reality made them quite appealing, especially amongst American audiences.19 Freeman, Richard. “The Mummy in Context.” European Journal of American Studies. Vol 4.1. (2009). 1. Despite the continued popularity of movies, Universal Studios was hit particularly hard by the depression, as it had been struggling to find success with many of its releases before the depression. This pushed them to try a new style of movie, one that would come to be known as horror movies, in the 1930’s.20 Freeman, Richard. “The Mummy in Context.” European Journal of American Studies. Vol 4.1. (2009). 1. The new genre was quite popular, with both Dracula, and Frankenstein movies drawing in large profits for the company. Universal hoped to follow up on their other successful undead monster movies with a new title, The Mummy. The Mummy was released in 1932, right after the height of the Ancient Egypt craze of King Tut and the peak of the undead movie genre’s popularity. Both aspects aided in the movies smashing success. The movie was so popular that The Mummy has been recreated and rereleased with the same title nearly once every generation since.

After their 1932 box office success, mummies were now proper horror movie monsters, they appear frequently in movies, on televisions and in cartoons. The fascination with Ancient Egyptian mysticism and the supernatural has kept mummies relevant for centuries. People are drawn to their unnerving, preserved state and enjoy toying with the idea of the Ancient world processing godly powers beyond our own. Like all trends the popularity of mummies and Ancient Egypt ebbs and flows, but people’s belief in the mystic is relatively consistent. People have come to accept the idea that something coming from Ancient Egypt can potentially have magical powers, in works of fiction especially. Movies use the public’s widespread belief a mystical Ancient Egypt to give their characters supernatural powers. Most don’t blink an eye now when something magical is said to come from Ancient Egypt in a book or movie, in fact many of us will take that as all the explanation we need to justify the person or object’s powers. To prove this point I will list handful of movies that have use this stereotype to drive their plots: Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark 1981, The Mummy, 1999, Suicide Squad 2016, Gods of Egypt 2016, The Mummy 2017. Movies’ consistent use of this stereotype regarding Ancient Egypt has continued the popular culture belief that started nearly 2 centuries ago; the belief in the idea that Ancient Egypt processed and was a catalyst for the mystic and the supernatural.